Narratives as Minor Architectures’ Repertoire: Affective Images and Haptic Architectural Visions

Almojábanas used to be a very popular sweet food in Al-Andalus. These fritters were made from a mixture of water, flour, and cheese, the fried in oil and coated in cinnamon and honey. In current day Spain, we can find its Colombian derivation in many cities as well as local variations in Valencia, Aragon or the Canary Islands. Traces, whether alimentary or not, are the trail left by the encounter between two different materials. When it comes to food, they are essential to ensure safety, as it is those physical traces left by distinctive industrial processes that laws, codes, and food safety protocols mainly address. Similarly, the traces of many other encounters not necessarily limited to food, but certainly decisive in the digestion processes, in the broad sense of the term, that characterise us, enable us to outline the basics of an architecture of environmentality. Spaces, as well as our capacity for action within them, are increasingly defined by the design of natural, social, and machinal sign(al) ecologies that orientate and mould our bodies, thus modulating their range of possibilities and behavior. Through almojábanas, some of the infrastructural semiotics underpinning the landscapes of contemporary nutrition are described.

Excerpts from the FOODSCAPES curatorial text, by Eduardo Castillo and Manuel Ocaña:

«(…) At a time when energy issues are more relevant than ever, food remains in the background, yet the way we produce, distribute, and consume it mobilises our societies, shapes our metropolises and transforms our geographies more radically than any other energy source.

Through an audiovisual project featuring five short films, an archive in the form of a recipe book, and an open research platform engaged in dialogue with audiences and experts, foodscapes explores the agro-architectural context of Spain — Europe’s food engine — to survey the present landscape of our food systems and the architectures that build them. By doing so, we look towards the future and ask ourselves about other possible models; ones capable of feeding the world without devouring the planet.

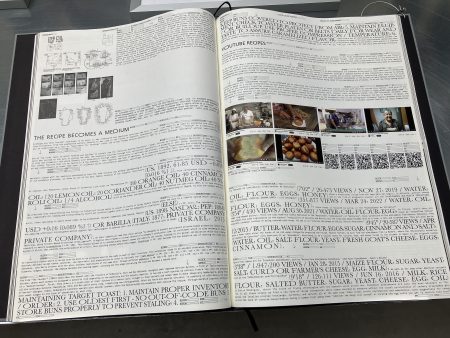

(…) The main hall of the pavilion houses a collection of documents, images, objects, technical drawings, texts, models, diagrams, and photographs. This visual display represents a documentary report of ten «total recipes». Wheras the short films offer an in-depth taxonomy of the different layers of the food system, the total recipes present case studies of how different dishes cut across the five layers, providing a cross-section of how the entire systems works.

Unlike standard recipes — which are often hemmed in by the technical constraints of our kitchens — the total recipes go further and encompass the whole infrastructural chain required to make the recipe.

Produced by an eclectic group of architecture firms, and shot by photographer Pedro Pegenaute, each recipe presents a «typical» Spanish dish as a catalyst from which to explore, trace, and document the architectures and territories that make it possible. in these foodscapes, food intersects with a myriad of topics such as soil exhaustion, non-human intelligence, self design geoengineering, neuromarketing, data infrastructure, food and pharmaceutical biopoolitics, waste circularity, animal rights, gender semiotics, and climate colonialism, among many others.»